Finding out the truth behind the great epics of the Trojan War is difficult. Writing was not widely used or developed in that part of the world, nor was the world as easily divided between “Greeks” and “Trojans.” Historic Troy, thought to lie on the northwestern Turkish coast at a sight known as Hisarlik, was first excavated in 1870 by the German Heinrich Schliemann. The theoretical date for the conflict that Homer based his epics around is somewhere between 1200-1100 BC, in the latter half of the Bronze Age.

It was the time of the great empires of the Assyrians, the Phoenicians, the New Kingdom Dynasties of Egypt, and the age of Moses. Greece was not the mighty and unified nation that built the Parthenon and killed Socrates; it was a scattered group of nation states loosely associated by bloodlines and trade ties, each proliferating as the Minoan empire suddenly disappeared around 1400 BC. Mycenae was the most powerful of the nation states, known for its opulent use of gold and exotic spices, but there were other kingdoms whose names are familiar: Sparta, Pylos, Ithaca.

Troy was a rather distant outpost loosely connected to the Hittite empire. The walled city was very wealthy due to its location at the mouth of the Dardanelles, a necessary land and maritime route for trade between the scattered lords of the Greek mainland and the hulking empires of Turkey and the Middle East. It led, eventually, to roads reaching the mysterious East.

Whether or not there was a dashing Prince Paris of Troy, or the astounding sexual being known as Helen, is stubbornly elusive. The great wealth of the Trojan state, combined with the Mycenaean rulers’ hunger for ever greater riches, probably contributed more to launching the thousand ships than a Spartan king’s broken heart. Whatever the case, there is indeed archaeological evidence at Hisarlik of a great city that was razed to the ground sometime at the end of the Bronze Age, one of many times the city was destroyed and rebuilt.

Homer, singing his epic poems in the 7th century BC, was the recipient of a rich cultural knowledge passed down orally; he was not the originator of these tales. It was his timing that made him immortal, however, as Greek was becoming a written language. The tales of the battle of wills of the gods, the anger of Achilles, and, of course, the stratagems of Odysseus had evolved over hundreds of years to become the national story of a world that was becoming more cohesive, more Greek.

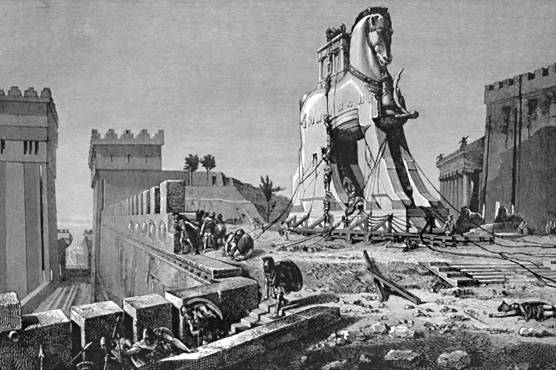

Despite the events’ significance in ending the age of Heroes, neither the story of the Trojan Horse nor the Fall of Troy have an epic of their own. They are mentioned briefly in the Odyssey and at length in the Iliad and are embellished much later by the Athenian playwrights. The story is thought to be the theme of two lost epics called the Little Iliad and the Ilioupersis. The tales do not appear, however, until several hundred years after they supposedly occurred. In part, it is this mystery that makes the Trojan Horse and the Fall of Troy so appealing. Over the millennia, many hands have tried to flesh out the skeleton of this compelling story bequeathed to us by the ages. The Trojan Horse Project is our effort to render the tale for today’s audience.